This post combines three things I love: teaching dogs cool tricks, helping people grow, and figuring out how to do it best. I want to show you how easily I work with both dogs and humans, where the skills overlap and how they differ, so you too can teach fun tricks and help your fellow humans get better.

Why assess understanding?

Assessing understanding is the key to improvement. If you know what you don’t know you can hone in on fixing that gap. Here’s the tricky part, though: understanding is fluid; without practice, our skills and knowledge atrophy. Thus, assessing understanding is a continuous process.

Understanding where someone is gets at a few parts of skill acquisition and refinement:

- As mentioned above, it helps you to find gaps in understanding or skills

- It helps you understand your subject better. For instance, if my dog understands that her back feet need to be on the bottom of the dog walk no matter what I’m doing, but she runs off when someone is too close to her, I can infer that she is uncomfortable with either that person or all people being too close

- It enables me to set my expectations correctly. If my young dog doesn’t yet understand that his feet need to be on the bottom of the dog walk, I know that I cannot be too hard on him when he comes off. I also know not to be as hard on myself

- It enables me to set them up for success. This is the other side of setting my expectations: it means my dog walks away from our session feeling like they were awesome at whatever we did. That means they’ll be excited to come back for more later

Differences between dogs and humans

I need to make some distinctions between how I work with dogs and humans before we proceed to my methods. There are many similarities but the differences are crucial

First, humans are smarter than dogs. What motivates you, fellow human, isn’t what motivates me, and often our motivations are complicated. Dogs are far easier than humans. People are more varied than dogs. Most motivators for dogs are treats and toys, some don’t even care what you feed them as long as they’re fed.

The next difference is that in teaching dogs, I’m working on some very discrete skills, like wait at the door and pick up a toy and hold it in your mouth. Teaching humans is less about teaching basic level stuff and more about building on existing skills. This is especially true with adults. You’re hardly ever teaching something new.

Obviously, language is a big difference. It’s very easy to declare intent to a human, but you also owe them explanations and clear communication of changes in plan. Dogs don’t get the benefit of knowing your plans, but you also don’t have to apologize with words when you make a mistake. They also don’t have to know when you make a mistake.

Finally, there’s a difference that I’ve left implicit thus far: respect. The base level of respect for a human is higher than for a dog. That isn’t to say I don’t respect my dogs, I do. But the respect shows differently. In humans, the respect means you aren’t so much about manipulating them into doing things, say by luring or bribing. Both species like it better when they think an idea is theirs, and both like to be left alone when they are stressed out, and they both require praise done right.

How do you assess understanding?

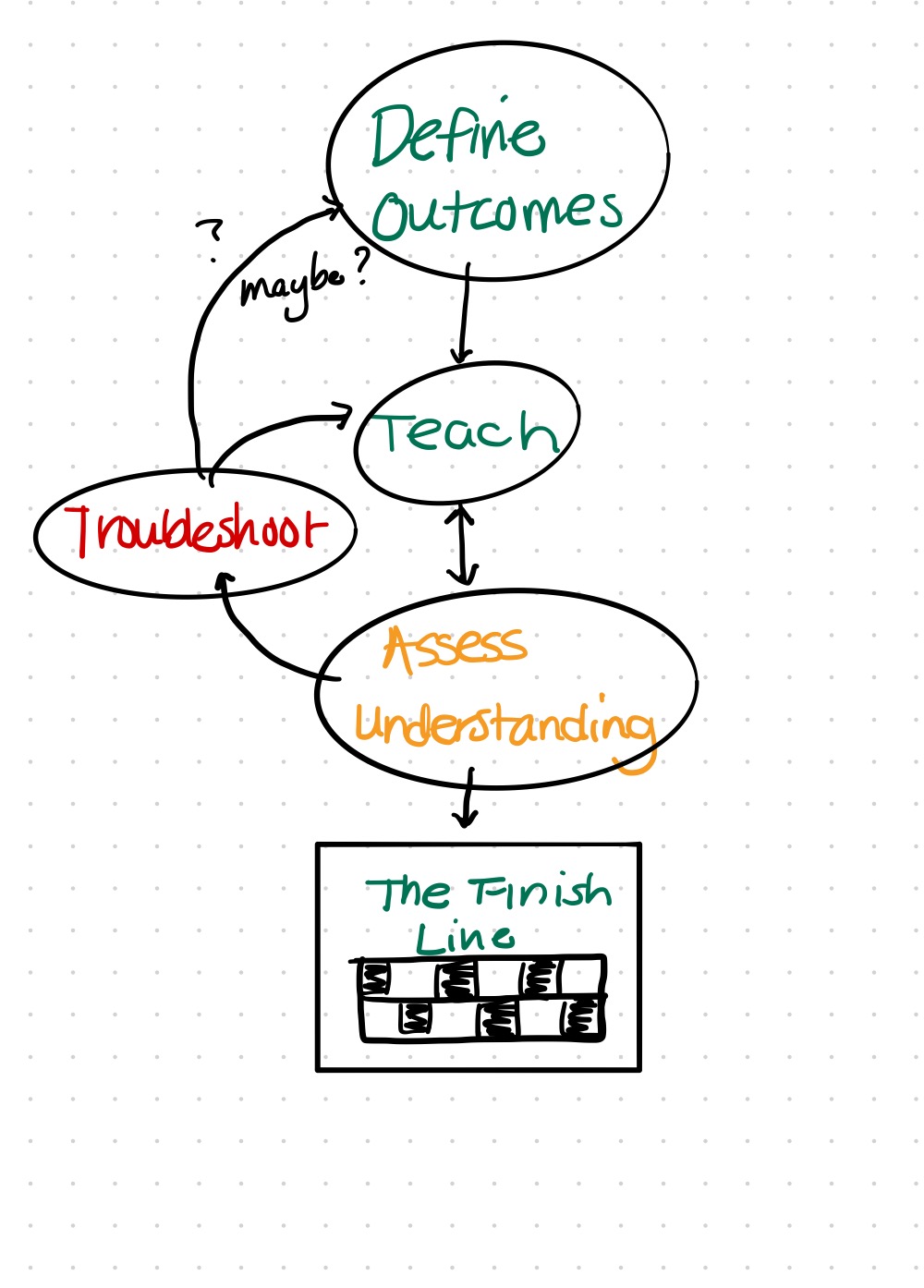

First, let’s talk about what you’re trying to achieve. From there, we will measure progress and troubleshoot.

Determining Outcomes

This will be about 10% of your teaching time, all at the beginning.

Ask yourself:

- What am I trying to teach?

- In what situations should they be able to perform this?

- What does success look like for this person?

There is more specificity to be achieved than this, but this is high level view of the behavior. During the Progress and Gaps sections, we’ll talk about the edge cases and details.

Humans

First, in humans. Let’s take a workplace example. I have a mid-level software engineer that I want to teach to design their own projects or features, from receiving requirements to execution. I want to teach them to do that so they can be promoted.

To answer my questions:

- I am teaching the skill of taking a bunch of work, understanding it well enough to break into parts, and then doing that work. I also want them to be able to document their steps so they can report progress.

- I want my employee to be able to use this skill on bigger and bigger projects.

- For my imaginary employee, who struggles with planning but not execution, I want to see the most improvement on the planning side.

This is a meta example, because we’re going through a similar process with this post.

Dogs

- I want to teach my puppy, Dash, to leave his back feet on the dog walk, A frame, or teeter (collectively called a contact) when he gets to the end of it.

- I want Dash to do this automatically at the bottom of any contact he encounters on any surface, at speed, indoors or out

- Success for Dash is doing this every time, no matter what is going on around him

Assessing Understanding

This is about 60% of your teaching time, going back and forth with your learner and adjusting yourself to their needs.

At this point, we know what we want to teach and we also know how we want to teach it (which I’m not covering here). Now it’s time to actually assess understanding and adjust our plans. Here’s what I ask repeatedly myself:

- What do they understand about the goal?

- Where are the gaps? How can I help fill them?

- Do they believe in their new skills or knowledge yet?

Humans

Our employee is learning about how to ask the right questions about the project, but they are confused by how to break it up into smaller parts. I believe they understand why breaking it up matters, but we need to delve into the how of that: thinking about milestones and what can be pushed to production first, what order things should be done.

They are still unsure, despite progress, so I am all about pointing out progress, showing the steps, and modeling behavior.

My next steps will be to work with them to break down the work, and also to keep building them up.

Dogs

This is where my dog actually is today in his training, so this is a realtime evaluation.

Dash understands where he should be. He understands that he should stay there. He knows how to do it, but he’s very unclear on the details. If he gets too excited, he fails. If I’m not moving just so, he fails. He isn’t sure how fast he can do and do it right. Even if I’m in the wrong spot, he may come off. We have lots of work to do.

For him, I’m thinking of specific things that cause him to fail and creating ways to help him be successful. A little less motion, a little less excitement, so he can win and leave our sessions feeling clever and happy. I’ll make it harder for him as we go. And I’ll be sure to be kind to him even when he’s driving me a little nuts, since he’s still new to this.

Troubleshooting

This will be about 30% of your time, mostly spent on your own figuring out what you need to do better.

Stuff goes wrong. Let’s talk about the common cases.

Backsliding

Our employee was executing well and now they’re not. Dash was hitting his contacts nicely, and now he won’t even get on the dog walk! What do we do?

Losing competence is usually about one of these things:

- Stress about the new skill

- Stress about something else entirely

- The goal (or, in dogs, the parameters of the behavior) wasn’t communicated correctly and they’re unsure, leading to (you guessed it) stress

What do you do? Find out what’s going on. Talk to your employee. When my cattle dog, Reba, started acting very scared of doing agility, I had to do ao much debugging. It turned out, after much thought and observation, that she was scared of things touching her that she couldn’t see: water dropping on her from the ceiling, static electricity, and large flies. We had to work for months to get her back in the ring.

After you find the why, how do you help? This is very individual, so it will be something to think through and adjust for your situation. Sometimes it’s as simple as clarifying the rules of the game. Other times, you may have change how you work with them or even declare an effort a failure. I have had to do that on a number occasions with tricks I couldn’t teach my dogs.

Checking out

This is also stress. Either you’re putting too much pressure on your learner, or they don’t feel confident and perhaps think you’re putting too much on them.

When they check out, you’ll need to assess your actions and figure out what went wrong. Lots of adjusting is needed here because while you had an implicit contract with your learner, they have now opted out. In humans, it’s tough conversations and hopefully you’ve built up trust to have them. In dogs, it’s introspection: asking yourself if you’re asking too much of your dog. When Reba was scared to do agility, I had to think hard if I should retire her. The answer turned out to be no, she likes it, but the time spent helped me clarify how she was motivated: she likes to work with me, she enjoys the teamwork best.

Dealing with my mistakes

We all mess up. Injecting stress and checking out are fundamentally a teacher’s mistakes, but there are others that are less damaging that I want to list here:

- Not communicating the goal, the context, and the reason to try this new thing well enough

- Not catching them doing well often enough

- Skipping steps while teaching, like me going from standing with Dash on the dog walk to running full tilt next to him instead of spending time at slower speeds

These mistakes may lead to bigger issues, so that’s why you need to be on guard to notice and stop them early. If you can correct yourself before they become big problems, you’ll stay on track.

The Finish Line?

This is the funny thing. Are we actually ever truly done? I’d say no, but that’s my core value of growth showing.

For the sake of your learner, you need to have a finish line and it needs to reflect what you laid out in the beginning. This is especially true with a person, who you can communicate with. You want to find a way to celebrate a new skill, and you want to let up on learning for a bit and let them enjoy some time to soak in what they’ve just accomplished.